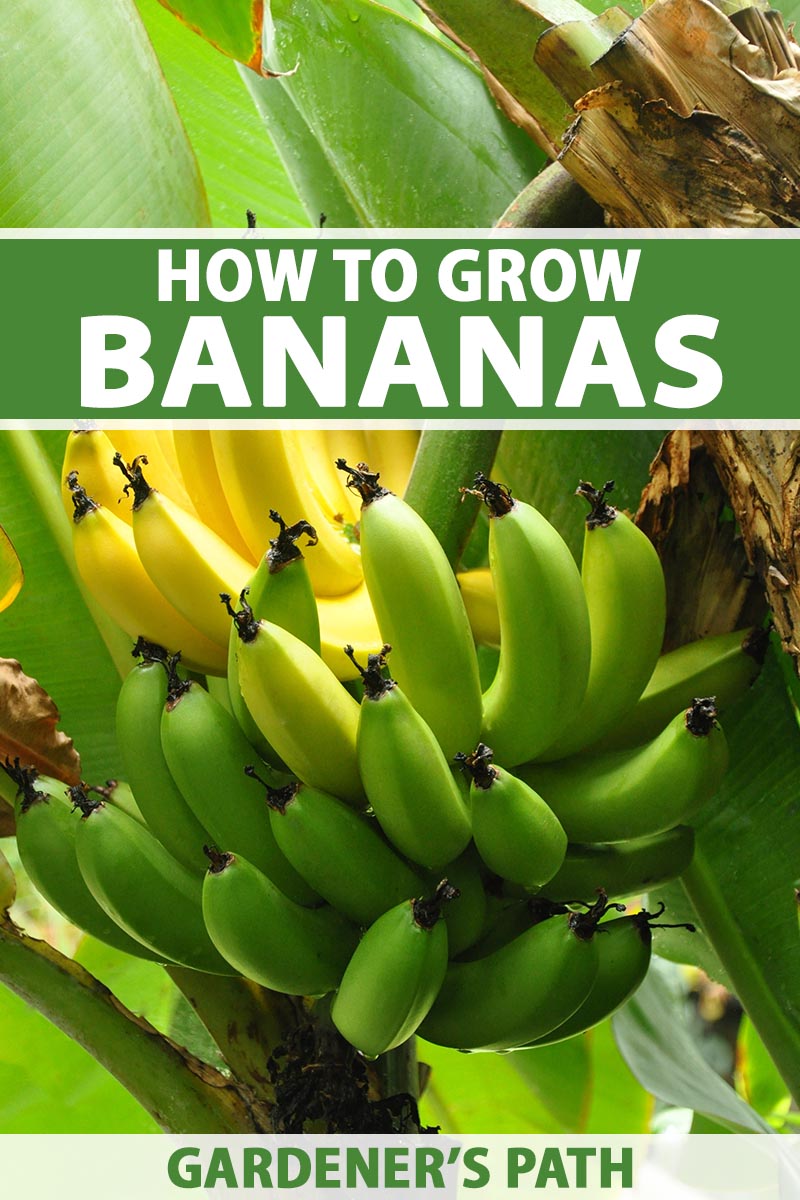

Musa and Ensete spp.

Although you are undoubtedly well acquainted with the banana, there’s more to this fruit than meets the eye.

We are all familiar with the long, typically yellow, sweet and starchy fruits that are loved the world over.

But did you know, according to the Guinness Book of World Records, the banana is the number one fruit consumed on Earth?

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

While there are more than 1,000 different varieties of bananas, the Cavendish, derived from M. acuminata, is far and away the most popular. It stores well, ships well, is resistant to fusarium wilt, and tastes great.

However, there are also red bananas! And did you know there are blue ones, too? Believe it or not, you can actually grow these, and our favorite, yellow, grocery store staple at home, too.

There are lots of great cultivars and species to choose from. Below, we will cover the basics and some general guidelines for growing bananas.

Read on to find out more about growing this celebrity among fruit trees. Here’s what I’ll cover:

What Are Banana Plants?

The plants that we call bananas are grouped into one of two genera, Musa and Ensete.

Musa contains Musa acuminata and M. balbisiana. The first of these two species produces the peelable, yellow fruit we put on our breakfast cereal or grab for a snack.

There are numerous varieties within this species, including those in the Cavendish group, aka the kind of banana we buy at the store.

The starchy fruits commonly known as plantains belong to Musa balbisiana.

The second genus, Ensete, is grown more frequently outside the US and it is full of diversity, too. The ornamental types you may have seen at botanical gardens often belong to this genus.

From a layman’s point of view, the two genera don’t differ greatly. The plants within both groups have large, soft, oblong leaves that fan out from a central trunk – more correctly called a pseudostem.

These plants produce an outsized cluster of tubular, pendant flowers housed within dusty purple bracts, within a large, tear-shaped bud. It’s this structure which ultimately produces the long, curved fruits we all recognize.

All the plants found within these two groups, and in fact, all the plants found within the family Musaceae are herbaceous.

So even though banana plants can grow very tall and produce what is essentially a trunk, they lack the woody growth that would technically make them trees.

In fact, the banana claims another title in this category, as it is among the largest herbaceous plants in the world.

Whichever genus they fall into, the species with edible fruit described under the common label “banana” are incredibly important food crops all around the world.

In Ethiopia, for example, E. ventricosum, commonly known as Ethiopian, or false, banana, is used to make a widely consumed porridge.

This species, in fact, is cultivated across Africa and prized for its ability to produce prolific amounts of food. The root, tender shoots, and fruit of the Ethiopian banana can all be eaten.

In Central and eastern Africa, about half of the available cropland is used to farm this species and its close relatives.

Cultivation and History

The center of diversity for the these plants rests in Southeast Asia. But the range of these popular plants has reached beyond these geographical confines for some time.

Recent research estimates bananas were introduced to South America via oceanic trading around 200 BCE!

Although frost limits the production of fruit, they are grown today in tropical latitudes all around the world.

In the 1600s, the Spanish began to cultivate the banana in earnest in South America. It was this effort that paved the way for commercial cultivation of the gargantuan herb in tropical regions of the continent.

The road to the banana’s fruity monopoly was a long and winding one, however, and not without some considerable hiccups. It wasn’t until the 1900s that popular cultivars began to emerge and take center stage.

The type that reigned supreme and propped up the “banana republic” economies of Central America was ‘Gros Michel,’ charmingly known in English as Big Mike.

Acres upon acres of clones of this seedless fruit were grown in vast monocultures and exported around the world.

Unfortunately, Big Mike got his comeuppance, as all monocultures inevitably do, when fusarium wilt hit plantations hard in the 1950s and virtually drove this variety to extinction.

Enter our beloved Cavendish.

Titan of commercial production, the Cavendish types are cousins to some equally loveable species and cultivars grown in homes and gardens everywhere.

Read on to find out how to grow these large and leafy plants yourself!

Banana Propagation

Generally speaking, there are three basic ways to propagate these fruit trees.

The individual needs of each cultivar or species may vary, so be sure to research the predilections of the plant you have selected while following these general guidelines:

From Seed

Believe it or not, the mighty banana can be grown from seed.

If you’re lucky enough to live in the tropical regions of the world you might have luck finding a wild banana with plenty of seed, but otherwise, there are numerous options for purchase online.

Make sure you buy from a reputable source, to ensure pest- and disease-free seed.

The fruits of wild types are full of small, round, black, glistening seeds. These were bred out of the cultivars sold commercially for eating because it’s not exactly a pleasant experience to get a mouthful of seed.

What this means for you is that if you grow these plants from seed, the fruit that you may eventually produce will also be full of seed. So think about that for a second before you begin.

If you’re undaunted, start by soaking your seeds in warm water for 24 hours. Bananas are tropical plants so they’ll germinate best if every step in this process is done in a warm environment.

Next, fill several four-inch pots with moist potting soil. Plant a seed one inch deep into each four-inch pot and cover with soil.

Water well and stand the pots in a brightly lit location where the temperature will stay around 80°F. Heat mats are very useful during this process as it can be hard to maintain the tropical temperatures the seeds love in the wrong latitude.

Make sure your seeds stay evenly moist while the germination is taking place. Do not let your pots dry out.

Seedlings should emerge in anywhere from two weeks to six months. Germination rates vary widely by cultivar.

Make sure your seedlings, once sprouted, stay warm and moist with regular watering.

After your seedlings reach a few inches high, transplant into larger pots filled with a mixture of compost and potting soil.

From Rhizomes

It’s possible to find the rhizomes, or roots, of banana plants for sale, too.

Bananas are monocots, meaning, they only grow up, not out. For that reason, you can’t take a cutting from a banana and propagate it.

Instead, the underground rhizomes are removed and potted up to grow a clone of the parent plant. These little clones have been lovingly dubbed “pups.”

To grow a banana from a rhizome, start in the spring or summer to ensure adequate light and warmth for growth. Bury it two inches deep in potting soil mixed with compost. They tend to like soil that is rich but freely draining.

Not sure what size pot to use? If your rhizome is three inches wide, use a six-inch pot to give it plenty of room for roots to grow.

Keep the soil moist, but not soaking, while the rhizome begins to sprout. Place the pot in a brightly lit location where the emerging foliage will receive six to eight hours of strong, indirect light.

Keeping your nascent plant warm while it sprouts will help too, so keep it away from any drafts or cold, unheated areas of the house. If you live somewhere in the cool, temperate realms, consider using a heat mat.

From a Pup or Sucker

If you have access to a mature banana plant, you can remove pups for propagation. Wait to remove it in this case until it attains about a third of the height of the main stem. This gives it time to develop strong roots as well.

To do this, use a long sharp knife to cut the sucker’s stem as close as possible to where it attaches to the central mother stem, and dig out the roots below.

This will mean you might need to brush the soil away from the base of the sucker a little bit. Make sure your cutting tool is sterilized before use by cleaning it with a little rubbing alcohol first.

To properly extract a transplantable pup from a potted banana, you’ll have to take your plant out of the pot, lay it on a tarp and excavate the pup’s roots using your fingers.

Once you’ve determined where mama’s roots end and baby’s begin, you can gently saw through the soil and material that holds them together.

You can either plant your pup directly in the ground or into a container.

Make sure to fill your new pot with rich, freely draining potting soil. Most potting soils will work fine, but it doesn’t hurt to add a few handfuls of sterile compost.

If you don’t have compost on hand, feed your tree immediately with a good quality fertilizer formulated for fruit trees.

Dr. Earth Fruit Tree Fertilizer

There are so many great options for organic fertilizer for fruit trees such as this one, from Dr. Earth, available via Amazon.

Transplanting

If you have a seedling, a recently divided pup, or a potted plant from the nursery, dig a hole as deep as the root ball in a spot with rich, freely draining soil.

Carefully lower the plant into the hole, making sure the bottom of the plant’s pseudostem is level with the soil. If your soil is sandy or gritty, add plenty of compost around your banana’s roots.

Water well before you backfill the hole and after planting. Finally, top dress with a few inches of good quality compost.

How to Grow Banana Plants

As with any other plant, the trick to growing healthy banana plants is to emulate the natural habitat these giant herbs love. Think warm, humid, and lots of light.

To grow bananas in the ground outdoors, you need to live in a frost-free Zone, or be prepared to properly winterize them.

Certain species, such as Musa basjoo, also known as hardy banana, can tolerate USDA Zones 5 through 10, but they’ll need to be wrapped in burlap and horticultural fleece once the frost arrives.

For an in-depth dive into all that, see our guide that discusses how to overwinter banana plants.

For most species of Musa and their close cousins in the Ensete genus, year-round, in-ground growing will only succeed in fertile, moist, humid conditions in USDA Zones 9 through 11.

If that describes your situation, lucky you! Start by locating a place in the garden that receives part shade to full sun and is sheltered from the wind. The soft leaves easily rip and tear in the wind.

When growing outside, it’s a good idea to leave at least eight feet on either side of your banana to really let it spread out. These monsters grow fast and go from rhizome to fruiting adult in less than a year.

If, like most of us, you live somewhere colder than the balmy climes of USDA Zone 9, never fear. You can grow many species in a pot, although you might want to take a look at the many dwarf varieties.

The pot can live outside on a warm patio during spring and summer, or take up permanent residence in a bright corner inside.

To grow a house banana, the instructions are fairly similar to planting outside.

First, use a pot that’s large enough for new roots to grow into. I like to make sure there’s about six inches on either side of the root ball.

Settle your plant in and fill the pot with plenty of sterile compost mixed with potting soil. Make sure the top of the root ball is level with the soil you’ve added. Water well.

Place your potted banana near a window that will provide six to eight hours of bright indirect light.

Some direct light is perfectly fine, so long as it isn’t all day. In fluctuating direct light, the foliage can get badly scorched.

If you don’t have a great spot, try hanging a grow light above your plant.

There are lots of stylish options nowadays, like this floor lamp that’s available from Gardener’s Supply.

Choose a room where your banana will stay warm. These tropical plants do not like drafts or significant temperature fluctuations.

They also prefer humid air, which most houses do not have! Daily misting with a spray bottle will help keep leaves vibrant and green.

If you want your banana to live outside for part of the year, make sure to move it only once warm temperatures have arrived. To minimize my plant’s stress, I move it outside when the temperature is reliably about 70°F and above.

I do this gradually, of course, giving the plant exposure to outside conditions for about an hour at first, and gradually extending this period over the course of a week.

Bananas do love full, hot sun, but they have to be acclimated to this kind of light, otherwise their foliage will become browned and burned.

Keep in mind that to promote fruit growth, temperatures really need to be about 80°F or more. For us northerners, that really means fruit production can only happen in a greenhouse setting.

When nighttime temperatures start to dip into the lower 50s again, it’s time to move your tender bananas back inside.

If you have a cold-hardy variety and are located no further north than a USDA Zone 5 growing region, you can winterize your banana using lots of insulation.

Finally, for growing indoors or out, consistent watering is key. These plants love moist, but not soggy, soil.

In virtually all places of the world except the tropical latitudes, this will necessitate almost weekly watering. For potted bananas, needing to water several times a week is more likely.

A good rule of thumb is to water when the top inch of the soil is dry. This will ensure the soil never quite dries out, but doesn’t get waterlogged.

When watering, do so thoroughly, until excess water comes out of the bottom of the pot.

If your plant is in the ground and you don’t receive an inch or more of rain per week, turn your hose on to a trickle and leave it at the base of your plant for an hour or two once a week.

Growing Tips

- Plant in rich, freely draining soils.

- Add compost when planting.

- Provide plenty of space, at least eight feet, for these rapid growers to spread outdoors.

- Site in a location with ample bright, indirect light.

- Water consistently, 1-3 times a week, depending on your location.

Pruning and Maintenance

When it comes to banana maintenance, there are just a few essential things to do to keep your plants in good health.

Make sure your plants are well watered and well fed, and they’ll mostly take care of themselves.

As herbaceous plants, bananas are relatively short lived. They pack a lot of activity into a very short amount of time. In fact, most species only take about 12 to 18 months to go from shoot to fruit under ideal conditions.

In total, the average lifespan of an adult plant in commercial production is about two years. This is partially because the stems only fruit once.

To keep plants as productive as possible, farmers remove and grow new suckers, cutting down the mother plant once she’s done producing.

In a garden setting or in a pot, and under your loving, watchful eye, bananas can live six years or longer. All of them will eventually fruit or start producing pups, after which the main stem will die.

Removing these pups, or suckers, is an important part of maintenance and ensuring the longevity of your plant. These little babies can cause overcrowding and rob your main plant of nutrients.

Dying or damaged leaves must also be pruned occasionally. These can be snipped with sharp pruners at the leaf’s base.

Be very careful not to damage the soft tissue of the main stem and make sure you use a clean, sharp pair of pruners.

Fertilization is another important part of maintenance as these plants are gluttons that require plenty of food. During the growing season, both indoor and outdoor plants benefit from monthly feeding.

Apply a balanced fertilizer with equal ratio of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium (NPK) to support leaves, flowers, and fruit, or make a compost tea.

I prefer to always use compost and compost teas for fertilization as this method ensures your plant receives important micronutrients too, like magnesium.

These kinds of fertilizers also work to improve the soil, which ultimately benefits your plants as well as the greater garden ecosystem.

You can learn how to make your own compost tea in our guide.

Whatever your method, always water well after fertilizing so nutrients quickly reach the roots.

Pay attention to how your plant responds to fertilizer, too. Some bananas need a little more food, others a little less, depending on the growing conditions and quality of the soil.

Signs of overfeeding include yellowed leaves, or whitish crystals that form a crust on the surface of the soil.

Lastly, water, water, water. Hailing from regions where rainfall is a near constant, these are inherently thirsty plants. As mentioned previously, they need watering at least weekly.

Banana Species and Cultivars to Select

To successfully grow banana plants, choose your cultivars wisely.

There are lots of different options with varying levels of cold hardiness, sunlight, and watering needs. Pick the plant that best suits your region.

There is a wide and wonderful world of bananas to choose from, folks! Red, yellow, maroon, you name it! Below are just a few of our favorites.

Blue Java

‘Blue Java’ was one of the bananas tantalizingly referenced in the introduction of this guide. For a little while, it has blue fruits!

This cultivar is a hybrid cross of M. acuminata and M. balbisiana. The latter commonly produces purple-tinged fruits in the wild.

While the fruits of ‘Blue Java’ do eventually turn the familiar, deep yellow when ripe, they’re a gorgeous, pale blue-green for a couple weeks prior.

‘Blue Java’ can be comfortably grown in USDA Zones 8 to 11. Also known as the ice cream banana, the fruits of this hybrid are especially sweet and quite gooey.

You can find ‘Blue Java’ available at Fast Growing Trees in a variety of sizes.

Dwarf Cavendish

An itty-bitty version of the world’s most beloved fruit tree, the dwarf Cavendish banana, another cultivar of M. acuminata, is available at Nature Hills.

Although this variety only grows up to six feet tall, it is more than capable of producing plenty of sweet yellow fruits each year, plus it’s small enough for indoor or outdoor growing.

This one is hardy in USDA Zones 9 to 11.

Ethiopian

Remarkable for its size and huge, red-ribbed leaves, Ensete ventricosum, or Ethiopian banana, can reach 40 feet tall in its native habitat. Outside of Central Africa, 20 feet is more realistic when grown in optimal conditions.

This species is longer lived than most, and does not fruit or produce suckers until it’s about five years old. The fruits themselves are hard and dry and inedible.

If you have the right climate and the space, this is a great choice for outdoor growing. Ethiopian banana is hardy in USDA Zones 10 to 11.

‘Maurelii,’ aka red Abyssinian banana, features the red ribs of the species plant and bright leaf undersides. It’s a bit more cold hardy, suitable for growing in Zones 8 to 11.

Plants are available from Fast Growing Trees in three-, five-, and seven-gallon containers.

Hardy

M. basjoo, or hardy banana, hails from China and can withstand temperatures found in USDA Zone 5.

It’s beloved for its toughness and truly gigantic leaves, which can be about nine feet long!

Although this is one of the smaller types, it can still grow up to about eight feet high. The fruits, if you manage to get any, are small and inedible.

You can find plants available from Fast Growing Trees.

Zebrina

Popular in horticulture, M. acuminata ‘Zebrina’ is an excellent choice for container growing.

Sporting beautiful, dark green leaves with red spots, this is one of the most striking cultivars around.

Hardy in USDA Zones 9 to 11, this is an indoor or greenhouse plant for most of us. The small-seeded, dark-skinned fruits this cultivar produces are sweet and edible.

Managing Pests and Disease

Unfortunately, the mighty banana is as well loved by us humans as it is by pests and pathogens.

Some species and cultivars are more robust than others, so take time to research the plant you choose to grow. Find out what its particular Achilles’ heel may be and keep a careful eye out for those afflictions.

Fortunately for those of us growing in temperate climes, a lot of the pests and diseases that attack these plants in the tropics cannot thrive here.

We just need to be concerned mainly with maintaining the environmental conditions these warmth-loving plants desire.

Pests

There are a number of pests that can show up to make a meal of your plants, here are some of the most common culprits you may run into:

Banana Aphid

As the common name suggests, the preferred host plant of this tiny, dark brown aphid, also known as Pentalonia nigronervosa, is the banana.

Found everywhere these plants are grown, it will feed on other tropical plants such as taro and ginger as well.

The insect is a phloem feeder, using its long mouthparts to pierce tender tissues and suck out the sap of its hosts. Feeding can kill young plants in large infestations, but typically, the damage from the aphids themselves is negligible.

Unfortunately, these aphids are the vectors of many significant diseases of bananas, including bunchy top virus. The honeydew produced by these aphids also creates a perfect environment for different types of mold to grow.

These aphids are reddish to dark brown and about 1/25 to 1/12 of an inch long. After seven to 10 generations of wingless aphids have been produced, adults will suddenly grow wings and disperse to other plants.

To check for banana aphids, examine the undersides and midribs of your plant’s leaves. Aphids often cluster and feed in these areas.

Releasing ladybugs is an excellent way to control these pests, as is a thorough rinse with a strong spray of water from the hose.

For more specifics, check out our guide to managing and eradicating aphids.

Banana Borer

A serious pest of bananas found everywhere these plants are grown, Cosmopolites sordidus is a small, dark brown to gray beetle that lays its eggs in the underground corms.

The adult is about half an inch long with a glossy shell and a long proboscis, as is common to weevils.

The larvae, once hatched, feed and tunnel, causing tremendous damage to the plant’s root system.

Although the larvae feed for only about two weeks before pupating and turning into adults, the damage can be extensive enough to completely ruin a banana’s rhizomatous mat and cause the plant to topple and fall.

The adult beetles do not cause much damage and commonly go long periods of time without food.

Unfortunately there are no effective chemical controls for the banana borer.

Burrowing Nematode

Native to Australasia, the burrowing nematode (Radopholus similis) is found throughout the regions where these plants are now commonly grown for the market.

Disseminated by the movement of infected plant material, these tiny worm-like parasites are incredibly destructive pests. Nematodes penetrate the roots of the plants and lay eggs inside, causing large areas of necrosis, or rot.

Symptoms of the burrowing nematode are largely invisible until the infestation is advanced, at which point the trees often tumble over. If the roots are examined, large black and brown lesions will be visible.

Movement of plant material within areas where the nematode is extant is strictly regulated in commercial production.

Strong pesticides can kill these pests but the preferred method of management is to make sure the plant material you purchase has been inspected and is disease and pest free.

Coconut Scale

Found throughout the tropical and subtropical regions of the world, coconut scale (Aspidiotus destructor), a major pest of bananas, is also sometimes found in greenhouses in more northern climes.

This insect is a circular to oval armored scale, yellowish to translucent in coloration. The adults are about two millimeters in diameter, so they’re very hard to see!

Coconut scale causes discoloration and disfiguration of the leaves. In large infestations, these insects can kill adult and juvenile plants.

Perform regular health inspections of your plant and look for scale on the soft tissue and undersides of the leaves. Occasionally, adult males may be visible. These look like tiny, reddish-brown flies.

Proper pruning and disposal of infested leaves is key to controlling these troublesome insects.

Wash affected plants using a cloth and soapy water to remove the majority of the infestation.

Carefully apply neem oil to the harder to reach parts of your banana plant to kill the remaining insects. Always follow all instructions on the back of the bottle.

Sugar Cane Weevil

The sugar cane weevil (Metamasius hemipterus) causes damage similar to the banana borer.

Eggs laid within the main stem of the banana hatch into small larvae which tunnel and feed on soft tissue, causing extensive structural damage.

The adults are about three-quarters of an inch long and have a distinctive pattern of red and pale brown to yellow patches on their glossy exoskeletons.

They sport the same long rostrum, or “nose,” that is common to weevils. These pests are spread via infested plant material.

This pest is more commonly found in large banana plantations. If you find it at home, destroy adults quickly by sweeping them into a cup of soapy water.

The troublesome larvae are unfortunately hard to reach and therefore hard to treat.

The easiest form of management is to ensure you buy inspected pest-free banana plant material and perform routine health inspections.

Disease

Unfortunately, banana plants can suffer from a number of troublesome diseases, too.

Generally, if you choose to grow just a few bananas you shouldn’t encounter too many of these issues.

The most severe problems emerge when these plants are grown in large monocultures.

Anthracnose

A common disease around the world, Colletotrichum musae, the species of fungi that plagues bananas, is commonly found in warm, wet environments.

The fungal spores survive in moist decaying leaves and enter the fruits through small wounds, causing black patches and discoloration. Sometimes, anthracnose can also cause fruits to ripen prematurely.

The spores are spread via almost every possible vector including animals, wind, and water, and are best eliminated by keeping your plants tidy and free of dead or dying material.

Bunchy Top Virus (BBTV)

This destructive virus causes the production of progressively shorter, narrower, and smaller leaves, forming a tight bunch of leaves at the top of an affected plant’s main stem.

Infected leaves are stained with darker green dots and dashes, in a pattern sometimes referred to as “morse code.” These leaves become brittle and often brown at the edges.

Plants infected by BBTV do not fruit. All species within the genus Musa are known to be susceptible, making this potentially the biggest threat to global banana production worldwide.

Currently extant in Africa, Asia, Australia, and the South Pacific, BBTV is spread by the pan-global aphid species Pentalonia nigronervosa, discussed above.

There is no known cure for this virus, but the transportation of plant material out of areas with endemic BBTV is strictly regulated.

If your banana comes down with this disease, destroy your plant immediately by burning and report it to your local agriculture department.

Fusarium Wilt

Panama disease, as it is commonly known, is the disease that caused the collapse of the ‘Gros Michel’ cultivar that once ruled the world. It is still at large.

But nowadays there are resistant cultivars, such as those in the Cavendish group.

The fungal pathogen that causes it, Fusarium oxysporum, is soilborne and causes yellowing of the leaves of adult plants, a foul odor as plant tissue rots, and finally, death.

Nothing can be done to prevent fusarium wilt. Once a plant is infected it must be removed and destroyed.

Mosaic Virus

This widespread virus, also known as cucumber mosaic virus, occurs across the temperate, tropical, and subtropical climes of the world and is common in a variety of crops.

It causes mottling and minor distortion of the leaves, but it does not gravely impact fruit development or production.

There is no known cure for this virus. The best method of prevention is ensuring bananas are not planted near the favored hosts of this disease, such as squashes or cucumbers.

The virus is spread by aphids who are blown from infected plants to non-infected ones.

Rhizome Rot

Rhizome rot can be caused by a variety of bacteria and fungi. In the tropics, Erwinia carotovora and E. chrysanthemi are two of the major bacterial culprits.

These bacteria live in the soil and enter through damaged tissue, causing the plant’s rhizome to soften and decay.

One of the first symptoms aboveground is a failure of rhizomes to sprout. Unfortunately there is nothing that can be done to prevent this soilborne disease from advancing once it has taken hold.

In the temperate climes, rhizome rot often occurs in cold, moist conditions and can be caused by numerous pathogens.

Keeping soil freely draining and properly winterizing outdoor plants, or moving bananas inside once cold weather arrives, can help.

Sigatoka Disease

There are two different fungi that may cause two different versions of the globally important sigatoka disease.

Black sigatoka is caused by the fungus Mycosphaerella fijiensis, and yellow sigatoka by M. musicola.

Both species of fungi cause defoliation and reduced fruit set.

Yellow sigatoka begins as small, pale green spots on the leaf which progress to become brown and yellow blotches.

Black sigatoka produces reddish-brown flecks which progress to become larger, darker spots, often with yellow rings around them.

As with fusarium wilt, the pathogens that cause this disease thrive in the warm, wet weather bananas love.

To control sigatoka disease, standard commercial treatment requires applications of some quite heavy-duty fungicides that are not commonly available for home growers.

Fortunately, this is not a disease that typically affects just a handful of plants. It is more frequently seen in the large monocultures cultivated by commercial growers.

As with most diseases, your best defense is to keep your plants healthy with adequate, timely watering and feeding.

Harvesting

If you ask me, home grown bananas should be picked when they’ve changed color to a deep yellow, or reddish brown – depending on the type you are growing – and are soft to the touch.

You can remove them singly from their cluster, but it’s best to harvest the entire bunch.

Many commercial growers will tell you to pick bananas when they’re light green, or just starting to turn reddish brown.

Since the fruits continue to ripen after they’ve been picked, you can leave light green fruit on a sunny windowsill and they’ll be ripe in about a week.

In my opinion, however, tree-ripened fruit always tastes better. Experiment. See what you find out.

When it’s time to harvest, use a very sharp knife, cleaned with rubbing alcohol, to sever the stem at the top of the fruit bunch. Just be careful not to damage the main stem of the plant in the process.

Preserving

Once your bananas are ripe there’s little you can do to preserve their sweet, soft, dense texture.

Putting this fruit in the fridge will change its flavor and alter the experience of eating it fresh. Freezing will also break down its fragile structure.

You can, however, refrigerate or freeze bananas if you just plan to use them in baking or to cook with later. Our sister site, Foodal, has a helpful guide to walk you through how to freeze the fruits.

If you want to preserve your home grown crop, try dehydrating slices of banana in a countertop dehydrator. Foodal has a guide to dehydrating fruits and veggies which can help you out.

Bananas cut into quarter of an inch slices generally take about 10 to 12 hours to dehydrate at 135℉.

Foodal also has lots more information about how to store bananas, which will buy you time while you sift through millions of mouthwatering recipes.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

There are an abundance of ways to use bananas once they’re ripe, or already getting a bit squishy.

Check out Foodal’s recommendations for some of our favorites, like this luscious layered trifle with oodles of whipped cream.

Most of these recommendations are for sweet treats, but there are savory recipes that call for this tropical fruit, too.

Surprisingly, cooked banana blends well with lots of different Thai or Indian spices, plus coconut, to create a lightly sweet curry.

And don’t discard those banana skins! Add them to your compost pile instead.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Herbaceous perennial | Flower/Foliage Color: | Creamy white, yellow, pinkish, light green/pale green, light green, spotted, variegated |

| Native to: | Africa, Asia | Tolerance: | Heat, poor soil |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 5-11, depending on species | Maintenance: | Moderate |

| Bloom Time: | Summer | Soil Type: | Organically-rich loam |

| Exposure: | Full sun to part shade | Soil pH: | 6.0-7.0 |

| Time to Maturity: | 18 months | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 8 feet or more | Attracts: | Ants, butterflies, hummingbirds, monkeys, skunks |

| Planting Depth: | 1 inch (seeds), root ball even with ground (transplants) | Uses: | Edible fruits, tropical ornamental landscape or houseplant |

| Height: | 2-40 feet | Order: | Zingiberales |

| Spread: | 2-10 feet | Family: | Musaceae |

| Water Needs: | High | Genus: | Ensete, Musa |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Banana aphid, banana borer, burrowing nematode, coconut scale, sugarcane weevil; anthracnose, banana mosaic disease, bunchy top virus, fusarium wilt, rhizome rot, sigatoka disease | Species: | E. ventricosum, M. acuminata, M. balbisiana, M. basjoo |

Grow your Favorite Fruit at Home

Don’t confine this superstar of the fruit world to the grocery store, give it a whirl at home! With the right amount of warmth, light, and moisture, you can boast home grown bananas.

Remember, it only takes 12 to 18 months to go from shoot all the way to fruit.

If you lack the heat or sun necessary for fruit production, choose a leafier ornamental cultivar whose foliage alone is enough of a crowd pleaser.

Situate it in a border where its large, luscious leaves can stand out against the bright colors of summer annuals, or give it a home on your patio.

Inside, the verdant foliage of a banana is a salve to a sunshine-seeking soul, especially in winter.

Do you grow bananas at home? Which species or cultivars? Tell us what issues you have encountered or what triumphs you’ve savored! Comments are always welcome!

To learn more about growing other tropical fruits, check out the following guides next: